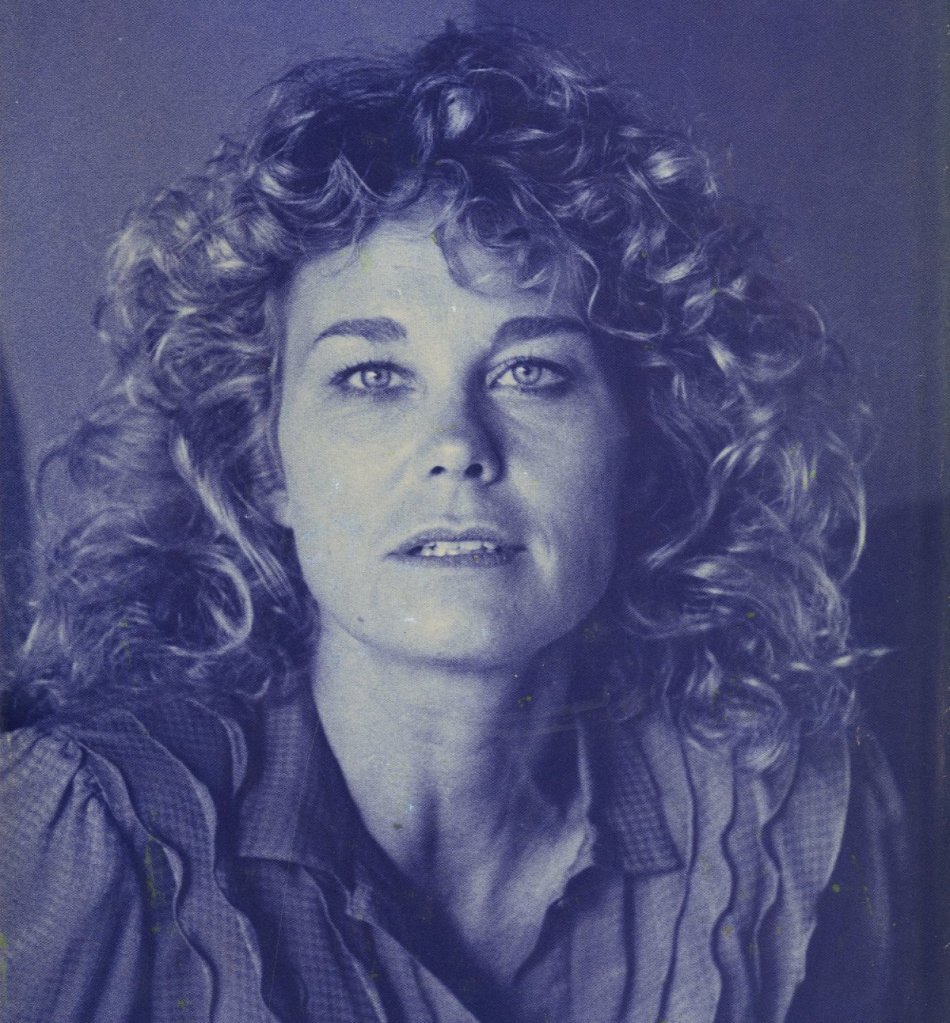

This article and accompanying interview with Frances Whyatt were written and conducted by Olivija Liepa, a Graduate Fellow at Barnard Archives and Special Collections for the 2023-2024 academic year. The Frances Whyatt papers are housed at Barnard Archives, and can be accessed through her finding aid.

In the Fall 2023 semester, I had the opportunity to process the papers of feminist novelist and poet Frances Whyatt for an archival description class at New York University. Whyatt, also known by the pen name Shylah Boyd, authored works of fiction such as American Made (1975), American Gypsy (1983), and A Real Man & Other Stories (1990). The author’s writing often draws on personal experience and addresses themes of gender, sexuality, and relationships. In processing her correspondence series, I noted that Whyatt predominantly split her time between New York City and the Florida Keys, where she grew up. The documentary traces of her life and activities also indicate her involvement with feminist organizations such as Women Against Pornography, Women Reviewing Women, and Forums by Women. Processing her correspondence gave me a glimpse into Whyatt’s community and her inner circles of fellow poets and feminist activists.

At Barnard, Whyatt’s papers contribute to a rich tapestry of collections that speak to a long and storied history of feminist movements and activities. As one of the founding members of Women Against Pornogrpahy (WAP), Whyatt’s feminist views and community have a particularly interesting legacy at Barnard, home of the 1982 Scholar and Feminist Conference on the Politics of Sexuality, often referred to simply as the Barnard Sex Conference. The Conference was both a culmination of brewing discourse within the feminist community and a catalyst to the Feminist Sex Wars that shaped the movement during the 1980s, dividing anti-pornography feminists and sex-positive feminists. The Diary of a Conference on Sexuality ironically likens WAP’s goal of regulating pornography to the sadomasochist community:

Despite their many points of disagreement, S/M and Women Against Pornography (WAP) are concerned with structure: S/M, in providing stylized and highly structured sexual interactions; WAP, in prescribing a politically acceptable framework for sex (13).

While since the 1980s the feminist movement has made greater strides towards views of sexuality centered on feminine pleasure, the debate surrounding the role of pornography and sexuality in feminist movements remains contested. As I processed Whyatt’s collection, I was struck by the apparent contradiction of Whyatt’s anti-pornography politics and her often sexually explicit writing. Her papers were donated by family members, Joseph Grannis and Eric Grannis, and while the processing archivists benefited from their input during the description process, they were not able to speak to Whyatt’s complex worldviews. Processing the collection for a class assignment, I sidelined my own positionality and curiosity, and the discrepancies remained unsolved.

When it comes to working with the papers of an individual, it is not uncommon for archivists who process collections to be working with the papers of a person they never met. Yet the work of describing a collection demands an interpretive framework, imagining an identity and voice of an individual, extracting information about them from the records they left behind. We write up biographies, create narratives surrounding arrangement of records, and determine strategies of appraisal based on what we deem to best represent the person. Neutrality and the myth of the archivist as an invisible steward of records are founding principles of the field, and they have not gone unchallenged by thoughtful archivists and scholars alike. Heather MacNeil and Jennifer Douglas argue that the assumption that a writer’s papers and their “original order” hold the potential to reveal the character and intentions of the writer, is flawed, and further, that archivists representing a writer’s records without imposing their own intentions on that representation is a near impossible task (28). Thus, as archivists we must do our work with extreme care when imposing interpretive frameworks.

One of the ways in which archivists can approach their processing work is through a framework of radical empathy. The call for radical empathy was first widely articulated by Marika Cifor and Michelle Caswell. Cifor and Caswell propose four interrelated shifts in archival relationships based on radical empathy: the relationship between archivist and records creator, between archivist and records subjects, between archivist and records users, and between archivist and larger communities (24). According to this framework, the archivist holds affective responsibilities to other parties, and should engage with these responsibilities with radical empathy: the ability to understand and appreciate another person’s feelings and experience, even when they may not always sit comfortably with our own.

After the finding aid for Whyatt’s collection was published, she reached out to the archive via email to indicate her interest in holding a conversation, specifically about her work within New York’s feminist movements. As I prepared for the conversation, I approached the interview with the methodology of radical empathy in mind. I spoke on the phone with Whyatt, who now resides in Massachusetts, on March 8, her birthday, and, fittingly, International Women’s Day. One of the hopes I held going into the interview was that our conversation could resolve the complex and entangled identities seemingly embodied in the Frances Whyatt papers. During our conversation it became clear that Whyatt, too, sat in the same complexity about her own politics and identity.

The framework of radical empathy enabled me to see Whyatt not as a static (archived) entity, but as a complex individual who herself sits with contradictions that are characteristic to the human experience. Archival principles often flatten nuance, archivists are expected to extrapolate a singular fixed truth or identity, when in reality such a thing may not even exist to begin with. As MacNeil and Douglas posit, “the writer herself is continually performing different versions of the self, and various other selves–friends, colleagues, and archivists among others–participate in shaping the meaning of the archive (39).” I am thankful to Whyatt for her ability to share her inner world and vulnerabilities during our conversation, thus making herself a more distinct voice in the social and collaborative text that is an archival collection.

The following paragraphs are an edited version of the conversation between Frances Whyatt and myself.

Olivija Liepa

Could you tell me a little bit about your experience of New York City in the ‘70s as a young writer and feminist?

Frances Whyatt

We were an energetic bunch. We knew each other by sort of reference, even though we hadn’t met. And then after we met, all sorts of things were assumed. I did not speak to friends much in terms of feminist politics. Feminism is sort of a guarantee because most of my female colleagues were feminist. With my close friend, feminist Susan Brownmiller, we didn’t talk about politics that much, except the assumption of a feminist framework. The politics were assured, known. We were more connected with our emotional feelings, competing against each other, whatever women do. It was just an interesting time, all sorts of things were going on, and we were involved in them. So it was a situation where I was going to women’s marches and making sure that my gay women friends were taken care of and all that. It wasn’t as if we were talking together and inventing a new feminist way of thinking. We were part of a feminist way of thinking. One of the original contemporary feminists, Betty Friedan, she was very forward in her thinking, but she was also very eccentric. We were adopting a lot of her views and discarding others, but she was very much a part of the original feminists. Susan Brownmiller, Gloria Steinem, we were sort of the second generation of that.

I mean, we were a groundswell. But we had people that we could identify with, we didn’t all of a sudden come out of the stars and said: “you will think this way,” or “you will be this way.” And I certainly have encountered a lot of male dominance issues, in my young life and in the workplace and everywhere else. I was a big rebel that way, I used to get fired or get into trouble, and also had a number of liberal-thinking men sticking up for me. I was a controversial figure at that time.

Olivija Liepa

Can you tell me more about your relationships with the other feminists in your group? Maybe how you met, or what you did together?

Frances Whyatt

Well, part of it was just geography. I knew Susan Brownmiller early on through a mutual friend, Judy Sullivan, who was also a feminist and wrote Mama Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. We became chummy. When I married for a second time, and my marriage split up, I spoke to Susan, who had moved to Jane street, and I said, “is there a place for me there, do you think?” and that happened. So I moved into the same apartment building as Susan and Florence Rush, who wrote The Best Kept Secret about child sexual abuse. There were several other women I knew in that building, it was in the west Greenwich Village area. It was a terrific neighborhood with all those marvelous brownstones right near the Hudson River, and so it worked out. I moved into an apartment there, met others who were so politically inclined, and grew from there. Hung out with other women in the movement and we all did well together, it was just easy. And then we became more and more politically involved with things of the times. I liked going to marches, political stuff was just kind of fun.

The assumption was always there. We all knew we were feminists, we all knew we’re gonna go to a march or whatever. Susan wrote on rape, for which she was absolutely terrific. Florence Rush wrote about child pornography. I mean, we all were writers in one way or another, I was a little unusual, because I was writing fiction, romantic fiction. We were all sort of colleagues. But we didn’t sit around and discuss political standards, and all that kind of thing to the nth degree. Basically, we talked about sales at Macy’s, from the sublime to the ridiculous. Did we read certain books, did we like them, why– things that writers talk about with other writers.

Olivija Liepa

Did you feel that you were not an outlier in your community, just because you wrote different kinds of texts than your colleagues?

Frances Whyatt

No, I can’t remember anyone ever being put down for what she was working on. That was just you working with what you think is correct. I’m working on what I think is correct. I don’t remember ever being attacked or addressed for the way I wrote. When you have a book out, you’re not looking to have to be close buddies with your other friends. You’re looking to see your book reviews in the New York Times and other newspapers. That was what people looked for. And what we looked for in each other, we looked for the book reviews, an important part of our professional life.

Olivija Liepa

On the topic of writers’ networks: can I ask you what you remember about living in Westbeth Artists Housing?

Frances Whyatt

Oh, Westbeth was terrific. It was “an artist’s housing complex,” and there were a lot of terrific people who were at Westbeth. Galway Kinnell, the poet, that’s how I met him, and he sort of mentored me. The poet Hugh Seidman, who I became totally best friends with for a while. There were a bunch of people who were terrific. It was great being there, the spaces were like large, long, wonderful loft spaces. Great hardwood floors. I mean, it was terrific. I think it helped me write, actually, to be around other writers and painters and so forth. And the way the space was doled out, I liked it a lot. And it was wonderful having all these creative people around. (laughing) I really liked Westbeth, I really did. It was a great life there with other creative folks. Everybody fighting over the mail, where the mailboxes were when it was time to find out about if your grant was accepted. It was the way a lot of us lived.

Olivija Liepa

Would you say that the kind of male dominance you mentioned was also present in the writers’ communities and circles?

Frances Whyatt

Yes, it was. You had Lowell, you had Galway Kinnell, other people, men who were extremely popular. Women did not get the attention, we were more known for Anne Sexton, Sylvia Plath, for neurotic, suicidal women. That was what attracted the patriarchy in some perverse way. If you’re healthy and pissed off all the time, doing well, and not suicidal and self-destructive, you didn’t get the kind of attention you should. We were still second-class citizens. It was a pain in the neck to be known only for being neurotic, particularly to someone like me, who is pretty cheerful and not suicidal. To bring forth that kind of energy, people like to put it down, think you’re a lightweight if you’re not seriously self-destructive.

It was a different mindset. In other words, women would become well-known and well thought of if they were totally self-destructive and talented, as opposed to being talented and life-embracing, positive. I think you pick up on that when you just think about the women historically, the Anne Sextons or Sylvia Plaths. To be “normal,” to be life-embracing and pretty upbeat was not thought of too well, if you were a woman in the arts.

Olivija Liepa

From your collection what I gathered is that you were an early member and activist with Women Against Pornography. Could you tell me about that?

Frances Whyatt

I was one of the founders. It was an odd kind of situation, because my [writing] work involved a lot of sexually explicit material. Pornography, as defined then, was a big negative. It was women sort of being exploited and “being bad,” as opposed to women being assertive and positively sexual. And I was into the latter. I wanted to be assertive about my own sexuality and people I was attracted to, and that was not a popular thing at the time. I pushed that. I mean, I have to say that yeah, I was cutting edge that way.

Olivija Liepa

So you weren’t personally categorically against pornography?

Frances Whyatt

Well, I didn’t think women being explicit in a positive way where there was nothing going against them was a bad thing. I thought part of pornography was the humiliation, the desecration of something that was otherwise good. Men exploiting women, basically, that’s pornography. Using sexuality for that, it was definitely a negative. In other words, pornography was a negative not a positive. Not women being in control, not having a bad reputation if you have sexual dealings or being with another person. It was the exploitation of women by men.

Olivija Liepa

Could you tell me a little bit about the founding of the group, what you may remember?

Frances Whyatt

Well, it was about…. We sort of sat around and talked about how men exploited women, and exploited them by being sexual in a certain way. It was a series of conversations. I remember Susan and I, that was on our minds. We, feminists who knew each other, and were in this movement thought, what’s wrong? If we want to get it on with a guy, why should we be thought of as less than? Instead of decent and decisive, we were somehow committing a sin, which was absurd and angering for most of us. This whole feeling that you can’t get it on without being less than. So that had an edge to it. Pornography was insulting. (pause) Does that reach you in any way?

Olivija Liepa

Yeah. Do you find that, do you still subscribe to those founding principles?

Frances Whyatt

Well, yes. I mean, I’m thinking decades ago, not currently. Because with me right now, I’m not concentrating on what I’m not doing. So really, I’m looking back to our movement and how we became involved, and how we came up with opinions. I mean, we were rebels. When I came of age, a woman had to watch her reputation, meaning she didn’t get laid, or, the assumption was, it was to protect your sexual privacy. Now it seems absurd. I mean, the whole thing seems somewhat absurd. But we’re so far away from when I came of age, you have far more more choices than I did.

I think the movement to a large extent was quite a success. But we certainly aren’t there yet. I mean, there still is discrepancy, and it’s always in the marketplace. It’s always about money. Bottom line, bottom line, women are still getting paid less than men. They still have less political power than men. But by the same token, we’ve come a long way from when I was coming of age, when the assumption [was] that women, of course, were paid less and of course didn’t have power. Now, it’s a big question. I mean, there were the Eleanor Roosevelts in my day, who divided all that, but who came out of the power of men. She was Eleanor Roosevelt, she was married to FDR, one of the most popular presidents of all time. She had an extraordinary life after FDR, and was into major issues. Then women evolved out of that sensibility, of wanting to do good and wanting to hold positions of responsibility, and so on. So the feminist movement didn’t just drop out of the cloud. It was a situation which built on generations of women. Very courageous women who acted for the good of mankind. That sort of thing.

Where does your generation stand on these issues?

Olivija Liepa

I think to some extent, we’re still having the same debates surrounding sexuality, especially at Barnard which has a legacy of sexual politics discourse. These are conversations that we’re still having, sex-positive feminism versus anti-pornography feminism. I myself would consider myself more of a sex positive feminist, but I am interested in weighing out the different sides of the discourse, because as you say that Women Against Pornography didn’t just fall out of a cloud one day, there’s such rich context from the violence in the free love movement to the of rise of pornography as a mainstream force in the 1970s. All of these conversations, I think they make a lot of sense.

Frances Whyatt

Yeah, it’s tricky. It’s not easily definable, as good, bad, all that sort of thing. Even to this day, where we have a lot more sexual freedom, there’s still situations which go back in time. Women still want certain realities to come into focus. So it’s questionable: as long as women have sexual feelings, and men have sexual feelings, you will have as easily the battle of the sexes. And to some degree, I mean, it’s just losing time if you put all your energy into that one. Because it’s such an emotional reality, really. (laughs) Funny you’re coming from Barnard. My brother was a professor at Columbia’s Teachers College, Joe Grannis. And I used to go up there to see him and look around, see how the feminist situation was going. I liked the idea of Barnard, always did. I mean, you guys are smart, political. Thank God for you.

Olivija Liepa

I think there is something significant to your papers being at Barnard, even in terms of institutional history. In 1982, there was a Conference on Sexuality, hosted by Barnard Center for Research on Women, which Women Against Pornography widely boycotted. And I’m wondering if you knew anything about that?

Frances Whyatt

About in ’82? … No, no. It doesn’t ring a bell. It may have happened, but I don’t remember it.

Olivija Liepa

I think Susan Brownmiller may have been more involved with it. If you don’t have personal experience, we can talk about something else.

Frances Whyatt

Right, yeah. I’m trying to think. In ’82 I was probably down in the Keys, living an alternate life. I mean, I had a couple of realities going for me. I’m from Islamorada in the Keys. I have a number of women friends of mine, my feminism to them was sort of like a guidepost: should they think this way, should they think that way? I mean, it was a whole different lifestyle down there, which I embraced wholly, I loved being glamorous and having fun and all that sort of thing. I didn’t particularly like their issues on civil rights, which were appalling.

Olivija Liepa

I understand. It’s interesting how we can embody so many different identities depending on context.

Frances Whyatt

Yes, that’s exactly correct. Another part of my identity certainly came out and the Keys, just having fun, dressing up, going to beach parties. We had the occasional serious conversation, but that wasn’t the norm (laughs). It was just a wonderful, hedonistic way of life. We had our own moral code, we tried to be good to one another, but that was about it. They knew I had this other life going for me. I needed them as much as I needed my feminist New York City life. So it was a little schizophrenic to say the least, going back and forth 1500 miles. Twice a year, I spent six months in the Keys and six months in New York City, and my work came out of both of those experiences.

I’m certainly not the only writer that embraced that kind of lifestyle. God forbid I should address myself in the same sentence as Ernest Hemingway, but he had that duality himself. He was from Illinois, he was running back and forth from there to Key West, and his work reflected that. There are a number of us. Tennessee Williams, same thing. Elizabeth Bishop. There was a big draw about the hedonism of the Keys. That is really hard to explain decently, it’s a marvelous place to drop out and gain all sorts of information that has nothing to do with the intellectual life you otherwise experienced.

Olivija Liepa

From what you’re saying, the fact that there was kind of a big community of writers drawn to the Keys, it does sound like there was something about it that could be intellectualized and represent the life of the mind.

Frances Whyatt

I don’t know about community of writers. I mean, I wasn’t hanging out with a lot of writers in Islamorada, I was hanging out with high school dropouts and people who got pregnant at sixteen, contractors or fishing guides. It was just an entirely different life than my so-called intellectual life in New York City. It was weird. I was accepted for being different in Islamorada. So when they had questions about things that were kind of intellectual and political and stuff, I would be asked about that, because I was accepted for being different in Islamorada. And when I went to New York, I thought differently, I wrote. I didn’t write in the Keys, all I did was take notes. But in New York, I became, if you’ll excuse the expression, a different person. I was all intellect and connection, and, you know, doing a job and writing constantly. So it was two lives, one fed into the other. It worked for me in some small way, I don’t recommend it for other people. It kept me fairly cheerful. My going from one lifestyle to another, I was generally always driving from the Keys back to New York. In that 1500 mile trip, I kind of settled myself from one lifestyle to another and enjoyed that.

I’m sure it molded my personality such as it was from one place to another. I was always looked at as having that intellectual life when I was in the Keys and people would ask me questions that had to do with another life. Same thing, and in opposite, what’s it like to be a certain way, go out and rock out, have a good time, mess around in the tropics. Maybe for somebody else it would be total paranoia, but for me it was both sides, and very enjoyable. As I’d say, I’m a fairly cheerful type, I don’t go into major long-lived depressions. I had the ride back and forth in which to adjust my interest.

Olivija Liepa

This conversation we’ve been having about the different identities that exist in different contexts makes me wonder about you as Frances Whyatt versus you as Shylah Boyd.

Frances Whyatt

(laughing) Well, I was kind of known as a poet. When I started writing prose, I got burned out on writing poetry, the discipline of it and so forth. I found when I was working as a temp and just getting a salary for a few months to avoid being broke in my 20s, I didn’t have anything to do. There was no demand for my time, I just had to sit at a desk. I started telling myself stories and typing them up. That started in my 20s, and that started the routine. I wrote a few short stories, or would tell myself stories on a typewriter. For some reason, they got published, so I started writing all these stories. American Made eventually came out of it. I thought I was writing a short story, and it just went on and on and on. I wrote the first draft in three months, and then went back, and cleaned it up. When I was writing stories, as opposed to poetry, which, a couple of words would take me a month, I was zipping up six, seven pages a day in prose. So I liked it, it was a much more natural thing for me. I was amazed when I found out that people seem to like my work, so I kept it up.

Boyd was my mother’s name. I wanted to take Boyd. I didn’t want to be recognized as yet another poet who’s tried to write prose, there was a whole joke in the publishing world about poets always trying to write novels and failing. So I changed my name. Shylah was a name that I had heard. I liked the sound of the name, so I took it, and I was comfortable with it. And certain people who know me from prose started calling me Shylah. And I was fine with that.

I mean, there was nothing really exotic about it. Except, I must say, Frances is a hard name for a female. Men, they become Frank: Frank Sinatra! But women, (groans) it’s Fran. I do not like that name. I like the idea of having a very feminine first name and Shylah, to me, was a very feminine sounding name as opposed to Frances. I don’t know. I just know that I would have liked to have been named Susan, or Alice, or Betty. I found those names more feminine, more acceptable. Just nuttiness on my part, really.

Olivija Liepa

You mentioned your writing process for American Made. Was there a relationship between your political work and your writing?

Frances Whyatt

No, I can’t say that there was. My political viewpoints were always that I wanted to be accepted and acknowledged as a human being who was doing something, not as a female, a girl: “oh, well, you’re good for a girl.” No, I hated that shit. So I guess, you know, I was a natural for the stuff that I was doing politically… There was nothing purposeful about it. My politics come out of my opinions, which were organic. I mean, I was that way when I was 12. I was always somebody who (pause) wanted to be known for doing something smart. Not for being just a pretty little girl who attracted all the boys. I just wanted to be known for all that stuff, as silly as that might seem. I wanted both, I wanted both worlds. I guess you could say I got it, to some extent, being in New York and the Keys. I mean, the Keys were about being pretty and about being acceptable and a lot of those things about being a nice girl, and New York was about being smart, intellectual.

Olivija Liepa

You don’t think they could have coexisted at the time in one place?

Frances Whyatt

Well, it did coexist. It just coexisted quietly. I didn’t think about what was involved with that, I just was who I was. In the Keys I was known as having this other intellectual, Yankee life kind of thing. And in New York, they knew that I was pretty intelligent, but I was from the South, from the Keys. So I was always acknowledged as having another life. Particularly, because most of my colleagues and buddies there were New Yorkers. It was Susan and Gloria, and all those people. They had a Yankee lifestyle, they couldn’t imagine living in the South.

There were things I hated about the South. I hated their position on civil rights. There, I was very political. And I very much wanted to have a decent life and country. I couldn’t– I hated the whole racism of the South. Hated it. That was a big deal. Even down in the Keys, they knew my position on civil rights. They put up with it, because I was otherwise doing well with them. That was a big deal for me.

Olivija Liepa

Can you recall a specific meeting or action that you went to?

Frances Whyatt

I went to a couple of marches. In New York, a bunch of them, some in Washington DC, that kind of thing. Both for women and for civil rights. There was the March in 1963, that was the big thing, going down to Washington. There, I was just 18. I was more than happy to be a part of that. I went, I protested and so forth. I always thought of myself as somebody who wanted justice and equality. There were civil rights groups that I was attached to. I belonged to the NAACP, obviously, SNCC–Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, there was that. I would just show up, and if I was asked to write something I would, or go somewhere, generally I would. You know, I was just a supporter. Women Against Pornography, I really did get active, and made sure of it. It was important. It wasn’t just pornography, it was a lot of other things that resonated with women. And sometimes with men as well, not that many, but there were some men who supported us and supported the organization.

Olivija Liepa

Was there discourse internal to Women Against Pornography? I know that around this time there was a kind of pushback from the sex-positive movement and opposition emerged to Women Against Pornography as well.

Frances Whyatt

Oh yeah, right. (sighs) I just thought it was stupid. I never became involved one way or the other with them, but I thought it was dumb that it was, in some ways, a reaction to us (sighs). Women Against Pornography, we’re not women hating men, obviously. They made a major statement in terms of the way women were treated, which was the bottom line for me.

We were supposed to be very supportive of prostitutes who wanted to get out of the life, but couldn’t. I remember going around to a number of the strip clubs, with my feminist friends and a couple of male bodyguards who were friends of ours to check it out. To me, it was just, ugh, it was sad and awful. There was a woman called the Happy Hooker, a Dutch gal who was a prostitute and enjoyed her work and her life and seemed to be in control of herself. But you didn’t see too much of that, you saw a lot of really unhappy women who were prostitutes because they had no choice. We thought of ourselves as an option for those women. We did talk to a number of them. (pause) I don’t know how successful we were, but at least they wanted to know about us. We weren’t changing any minds that I know of. We were just there as an option.

You have to understand that many of these women were completely defined by their pimps, by their earlier lives with dysfunctional families. This was their life. Our feeling was: if you’re a happy whore, that’s great, but if you’re being used and abused, that isn’t great. As opposed to saying that prostitution was wrong, it was being used and made miserable that was wrong. We weren’t making moral judgments about what they did with their bodies. Actually several of the feminists that I knew had tried turning tricks for a while, then got out of it, got enough money together and got education and all that stuff. You know, they didn’t seem to be too negatively influenced by it. (pause) Prostitution’s a tricky subject. You know, Gloria Steinem made the comment that wives were prostitutes. Marriage, the whole concept of women being taken care of by men, she saw a relationship between that and prostitution, which is bullshit. There was that way of thinking in those days. I think it was short-lived.

With Women Against Pornography we marched several times. We opened up our office right off of Times Square. Oh, it was weird. The whole thing was weird because (pause) on the one hand, I was for honest, explicit sexuality. On the other hand, I couldn’t stand the way women were treated or looked at in terms of their sexual freedom. It was like being both at the same time, because I was a woman who wrote explicit sexuality, and wanted it on my own terms, as opposed to what put women down or was pornographic. To me pornography was about women getting abused. So here I was sticking up for women, not to be abused and yet writing explicit sexuality. I know it’s a stretch, but I wanted to see women, I want to use the word power, but you know, accepted. It should not be anything that’s denigrated. Human sexuality is a positive thing. Men can have it but women can’t? That’s horseshit. So that basically was my position. Women should be accepted and respected. And sexually active at the same time.

I mean, you’ve inherited a lot of freedoms from other generations of women. It’s hard to think of, say, not being able to go to a women’s college, not being able to write books, not being able to do a lot of things because of some standards that you’re supposed to apply yourselves to. I would like for other women to be able to express themselves, whether they’re wives, or writers, or painters, or lawyers, whatever they wish to do. Not to be held back the way women were held back for eons, not being able to achieve things that they would otherwise be able to achieve.

References:

Caswell, Michelle, and Marika Cifor. 2016. “From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics: Radical Empathy in the Archives.” Archivaria 81, 23-43. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/687705/pdf.

Diary of a Conference on Sexuality. 1982. Pamphlet. http://www.darkmatterarchives.net

/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Diary-of-a-Conference-on-Sexuality.pdf. ↩︎

Douglas, Jennifer, and Heather MacNeil. 2009. “Arranging the Self: Literary and Archival Perspectives on Writers’ Archives.” Archivaria 67, 25-39. https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/view/13206. ↩︎